03_Buried

Printable zine version:

Ladies of Llangollen.

Eleanor Butler (1739–1829) & Sarah Ponsonby (1755–1831).

County Kilkenny, Ireland & Llangollen, North Wales.

In 1768 Eleanor Butler (b.1739) met Sarah Ponsonby (b.1755), becoming fast friends and later sharing an intimate correspondence. A decade late, whilst Eleanor’s brother conspired to marry her off and Sarah’s guardians planned to send her to convent, the two hatched a plot to abscond to England. Dressed as men, armed with a pistol and a dog they fled into the night. Sarah fell ill before reaching the ferry and they were soon discovered. With a second escape delayed by Sarah's illness, Eleanor hid in Sarah’s bedroom with the aid of a sympathetic maid, Mary. The relatives soon realised that keeping the two apart was more trouble than it was worth. In 1780 Sarah, Eleanor and Mary travelled to Wales, and bought the gothic house Plas Newydd, near Llangollen. Sarah and Eleanor shared a room, a bed and their lives for the next 50 years. They transformed their home into a vast collection of books and woodcarvings. They signed all letters together, inscribed their books and glassware with both initials and owned a succession of dogs named Sappho. Since their first attempted elopement, gossip had spread, enough to earn them visits from Wordsworth, Byron, Anne Lister and even Queen Charlotte.

“William Wordsworth celebrated the ladies in a sonnet, 'Sisters in Love'; the painter and poetess Anna Seward wrote poems about their 'Davidean friendship' and painted portraits of them; Anna Lister wrote in 1822: '... I cannot help thinking that surely it was not Platonic. Heaven forgive me, but I look within myself and doubt.' Diarist Mary Elizabeth Lucy recorded: '... these two ladies looked just like two old men ... they were so intensely devoted to each other that they made a vow, and kept it, that they would never marry or be separated, but would always live together never leave or sleep out for even one night.”

(Coyle, 2015, p.20)

They are buried together at St Collen’s Church, Llangollen, alongside Mary.

Glamorgan Pottery (c. 1815–25) 'Ladies of Llangollen' [Blue pattern plate] At: Amgueddfa Cymru, Wales.

Thomas, J. (c. 1875) 'Plas Newydd, Llangollen' [Photograph] At: The National Library of Wales Catalogue.

Biblio:

Coyle, E. 2015. LIFESTYLES: THE IRISH LADIES OF LLANGOLLEN: 'The two most celebrated virgins in Europe'. History Ireland, [online] 23(6), pp.18-20. Available at: <www.jstor.org/stable/43598746>

Darling, L. 2016. The Story of the Ladies of Llangollen. [online] Making Queer History. Available at: <www.makingqueerhistory.com/articles/2016/12/20/the-story-of-the-ladies-of-llangollen> (Accessed: October 9, 2022).

In Zine Figures:

1. Glamorgan Pottery (c. 1815–25) 'Ladies of Llangollen' [Blue pattern plate] At: Amgueddfa Cymru, Wales.

2. Lynch, J.H. (c.1870s) 'Portrait of The Rt. Honble. Lady Eleanor Butler & Miss Ponsonby 'The Ladies of Llangollen' [Lithograph] At: The Welsh Portrait Collection.

3.'Llangollen' (n.d.) [Photograph] At: National Archives, London. INF 9/641/7

Anne Lister.

1791 - 1840.

Shibden, West Yorkshire, England.

Horner, J. (c. 1830) ‘Portrait of Anne Lister‘. [Oil on canvas]

Mrs Taylor of Halifax (c. 1822) ‘Anne Lister of Shibden Hall‘. [Watercolour painting]

“I love and only love the fairer sex and thus beloved by them in turn, my heart revolts from any other love than theirs.”

Diary of Anne Lister, 29th January 1821

Anne Lister was a prolific diarist and lesbian in 19th-century England. Highly charismatic, and intelligent, Anne was a consistent and unrepentant rule-breaker. Dressed in an all black, largely masculine style, she was dubbed ‘Gentleman Jack’.

“We were talking of my dress. She said people thought I should look better in a bonnet. She contended I should not, & said my whole style of dress suited myself & my manners & was consistent & becoming to me.”

Diary of Anne Lister, 10th May 1824.

Whitbread, 1992, p.342.

She met her first love, Eliza, at boarding school, and later Mariana Belcombe, a woman whom she would remain entangled with for many years. Though separated by 40 miles, the two would trade visits and letters until 1815, when Mariana married, leaving Anne distraught. However, this wouldn’t last, as a year later they resumed their relationship. Anne wrote:

‘Sat up lovemaking. She [asked me to swear] to be faithful, to consider myself as married. I shall now begin to think and act [as] if she were my wife.’

In 1922, Anne and Mariana visited the Ladies of Llangollen. In 1923 their affair ended and three years later Anne inherited Shibden Hall from her uncle.

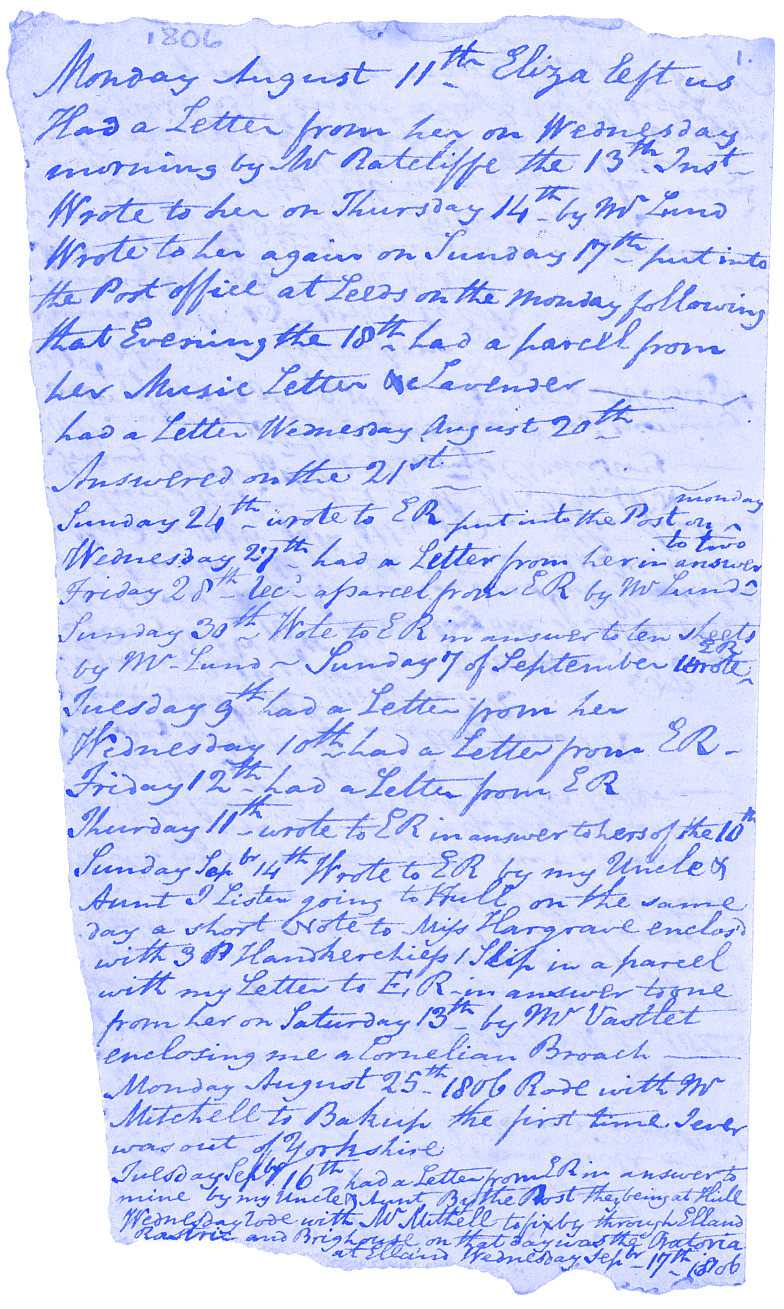

11-Aug-1806 Entry [sh-7-ml-e-26] - Anne’s first entry

In 1832 Anne would become reacquainted with the heiress Ann Walker (they had met in 1815). On the 10th of February 1834, the two exchanged vows and a fortnight later, rings. On Easter Sunday the two took communion together, considering themselves married from that point on. Anne and Ann lived and travelled together for the next 6 years until Anne’s early death. In her will she gave Ann a life interest in Shibden Hall.

11-Aug-1840 Entry [sh-7-ml-e-24_0174] - Anne’s last entry

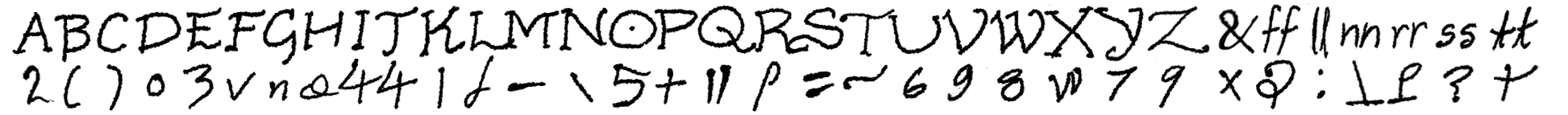

Her diaries religiously chronicled 34 years of her life, containing over four million words written in a secret code of her own making named ‘crypt-hand’.

“Lister's diaries have also been called the Rosetta Stone and the Dead Sea Scrolls of lesbian history, and websites discussing Lister often refer to her as the “first modern lesbian.”

Roulston, 2013, p.267.

”Queerness has always been associated with codes, with hiding, deciphering, and strategic revealing. Lister's diaries are both a key—with sections literally written in code—and a transparent, explicit, and unashamed representation of lesbian desire. This makes Lister a symbolic conflation of past and present.”

Roulston, 2013, p.268.

“Lister's encoding of her diaries is the first marker of her complex relationship to both her sexual identity and her gender presentation. By its very presence, the code signifies an awareness of the forbidden, taboo, and potentially shameful quality of her writings. Anita Rowanchild suggests that Lister's decision to refer to her code as a “crypt,” when the more common term would be a “cipher,” “connotes the tomb, a place of preservation, of ghosts, and of silence” (2000: 206). The code is also there to make the content inaccessible to the casual reader, and yet it is a diary, an already private document. From whom, then, is Lister hiding?”

Roulston, 2013, p.272.

Anne’s diaries would remain encrypted until, years later, John Lister found the diaries behind oak panelling and with his friend Arthur Burrell, cracked the code. Poignantly, it is through the word ‘hope’ (note Lister and Burrell felt confident on ‘h’ and ‘e’, and through a note from Anne reading “In God is my….”, the two confidently guessed the final word in crypt hand was ‘hope.) that the pair were able to decipher the diaries.

Now, the contents of Anne’s diaries, described in pretty lurid detail (amongst the day-to events) her lesbian identity, desires, and adventures into said desires. Burrell told Lister to burn the diaries. Instead, he hid the diaries once more. It is thought that Lister himself was secretly gay (in 1885 male homosexuality was illegal.) It is perhaps ‘hope’ for a later, kinder time, that kept him from destroying them.

The diaries and the key were later rediscovered by the Borough librarian and donated as the type-script ‘A Spirited Yorkshire Woman’ to the British Museum. Under the proviso that ‘unsuitable material should not be published’ Phyllis Ramsden and Vivien Ingham deciphered the diaries, making a chronology of Anne’s life and summaries of the contents (Harding, 2019, p.235) The Guardian reopened the call for researchers in 1984. Helena Whitbread joined The West Yorkshire Archive Service, and finally, Anne Lister’s diaries were decoded and published, ‘Gentleman Jack’ published at last in all her lurid lesbian detail.

The West Yorkshire Archive Service currently hosts scans and transcriptions of Anne Lister’s diaries. In 2011, the diaries were added to the UNESCO Memory of the World Programme.

“There is a process of identification we engage in with queer historical figures, creating what Valerie Traub calls “lines of transmission of desire and culture” (2002: 352). Having no bloodline linking us to the past, we seek out a genealogy through affinity and identification; we look for those queer figures who can help us invent and create our own history, but we also yearn for a past that can give us a future, a modern past, so to speak.”

Roulston, 2013, p.268.

Biblio:

Anne Lister – Diary Transcription Project. 2019. West Yorkshire Archive Service Blog. Available at: <www.wyascatablogue.wordpress.com/exhibitions/anne-lister/anne-lister-diary-transcription-project/> (Accessed: September 15, 2022).

Harding, J.G.R. 2019. “The Other Anne Lister,” The Alpine Journal, pp. 234–240.

Roulston, C. 2013. The Revolting Anne Lister: The U.K.'s First Modern Lesbian. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 17(3-4), p.267-278.

Medhurst, E. 2020. From Anne Lister's closet: The LBD (Lesbian Black Dress). Available at: <https://dressingdykes.com/2020/08/14/from-anne-listers-closet/> (Accessed: September 18, 2022).

Medhurst, E. 2021. From Anne Lister's closet: Top hats or Bonnets?, Dressing Dykes. Available at: <https://dressingdykes.com/2021/10/01/from-anne-listers-closet-top-hats-or-bonnets/> (Accessed: September 18, 2022).

The secret diaries of Anne Lister - cracking the crypthand code. 2021. Visit Calderdale. Available at: <https://www.visitcalderdale.com/the-secret-diaries-of-anne-lister-cracking-the-crypthand-code/> (Accessed: September 18).

Whitbread, H. 1992. I Know My Own Heart: The Diaries of Anne Lister, 1791-1840. New York: New York University Press. p.342.

In Zine Figures:

4. Shibden Hall

5. 11-Aug-1806 Entry [sh-7-ml-e-26] - Anne’s first diary entry

Charity Bryant and Sylvia Drake

Charity Bryant (1777–1851) & Sylvia Bryant (1784–1868).

Vermont, USA.

'Silhouettes of Sylvia Drake and Charity Bryant of Weybridge, Vermont' (c. 1805–15) [Ink, cut paper, hair locks] At: The Henry Sheldon Museum of Vermont History.

Popova, M. 2014.‘Charity and Sylvia’s headstone at Weybridge Hill cemetery’ [Photograph] Available at: <https://www.themarginalian.org/2014/08/13/charity-and-sylvia-marriage/>

In 1807 Charity Bryant (b.1777) moved to the small frontier town of Weybridge Vermont, where she would meet Sylvia Drake (b.1784). Charity, a skilled tailor hired Sylvia as her assistant. After only a few months, Charity asked that Sylvia move in with her:

“I not only want you to come to assist me but I long to see you and enjoy your company and conversation,” On July 3rd 1807, Sylvia “consented to be my help-meet and came to be my companion in labor ”.

They soon after built a home and tailoring shop and for the next 44 years.

Charity ordered a ring for Sylvia and the two made the journey back to Charity’s home in Massachusetts. Her sister Anna wrote:

“I need be under no apprehensions concerning your welfare while so dear and faithful a friend as Miss Drake is your constant companion,”

Sylvia wrote to her mother:

“She is everything I could wish.”

One of Charity’s nephews wrote in the New York Evening Post:

“If I were permitted to draw aside the veil of private life, I would briefly give you the singular, and to me most interesting history of two maiden ladies who dwell in this valley. I would tell you how, in their youthful days, they took each other as companions for life, and how this union, no less sacred to them than the tie of marriage, has subsisted, in uninterrupted harmony, for forty years...I could tell you how they slept on the same pillow and had a common purse, and adopted each other’s relations, ... I would tell you of their dwelling, encircled with roses, which now in the days of their broken health, bloom wild without their tendance.”

Bryant, 1850.

They would never spend a night apart until Charity’s death in 1951. When Sylvia followed in 1868, their families buried them under a shared headstone.

“Although Sylvia and Charity lived a quiet life, far from the bustle and commotion of the nineteenth century’s growing cities, they did not live in secret. Everyone who knew them understood that they were a couple and viewed their relationship as a marriage.”

Cleaves, 2014, p.X.

“Queer history has often focused on the modern city as the most potent site of gay liberation, since its anonymity and living arrangements for single people permitted same-sex-desiring men and women to form innovative communities. More recognition needs to be given to the distinctive opportunities that rural towns allowed for the expression of same-sex sexuality.”

Cleaves, 2014, p.XIII.

“Cleves — who chanced upon Charity and Sylvia’s story by complete accident while browsing a local history museum — reflects on the broader importance of mining history for evidence of social phenomena we mistakenly believe to be unique to our age: “The research process has left me more sure than ever that there are countless pieces remaining to be found, if not from Charity’s and Sylvia’s lives then from the lives of other lovers who lived outside the norms. Their stories have been hard to see because they confound our expectations. We see each story as one of a kind, defying categorization. Taken together they tell a history we are only beginning to know. The most remarkable element of Charity and Sylvia’s life together, in the final assessment, may be how unremarkable it was.”

Popova, 2014.

Biblio:

Bryant, W. 1850. Letters of a Traveller, or Notes of Things Seen in Europe and America. New York: George G. Putnam.136, qtd. in Cleves, xiv-xv.

Cascone, S. 2018. A Rare Image of One of the Earliest Known Same-Sex Unions Goes on View at the Smithsonian. [online] Artnet News. Available at: <https://news.artnet.com/art-world/19th-century-same-sex-union-smithsonian-1293428> (Accessed: October 10, 2022).

Cleves, R. 2014. Charity and Sylvia. Oxford: OXFORD UNIV PR. p.x-xiii.

Dabhoiwala, F. 2015. The secret history of same-sex marriage. [online] The Guardian. Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/jan/23/-sp-secret-history-same-sex-marriage> (Accessed: September 19, 2022).

Popova, M. 2014. Charity and Sylvia: The Remarkable Story of How Two Women Married Each Other in Early America. [online] The Marginalian. Available at: <https://www.themarginalian.org/2014/08/13/charity-and-sylvia-marriage/> (Accessed: September 10, 2022).

In Zine Figures:

9.'Silhouettes of Sylvia Drake and Charity Bryant of Weybridge, Vermont' (c. 1805–15) [Ink, cut paper, hair locks] At: The Henry Sheldon Museum of Vermont History.

Elizabeth Etchingham and Agnes Oxenbridge

c. 1480-????

Etchingham, England.

Brass of Elizabeth Etchingham and Agnes Oxenbridge (c.1480) [Brass memorial] At: Etchingham Parish, Sussex, UK

In Etchingham Parish one might find a spot for a sapphic pilgrimage. The Brass of Agnes Oxenbridge and Elizabeth Etchingham is a memorial to two women buried there together.

“Elizabeth appears on the left with her hair down and she is smaller than Agnes. This is likely representative of her being both unwed and young when she died in 1452 in her mid-twenties. Agnes is shown on the right … she was in her fifties when she died in 1480. Evidence for both women remaining unwed in the lack of head coverings, lack of records (both marriage records and records of their lives as was often the case with single women), and lack of any mention of husbands on the memorial (Bennett, 2011, p133). She also describes how this brass was designed in the style of contemporary memorial brasses for married couples, but with additional intimacy. Unlike the contemporaneous brasses, which often show couples looking straight ahead, Agnes and Elizabeth face each other and look into each other’s eyes (Bennett, 2011, p134). It was unusual that Agnes be buried with Elizabeth instead of in the Oxenbridge mausoleum, but both families must have agreed for it to have happened and in turn chosen to commission such an intimate memorial (Bennett, 2011, p133).

Woodley, 2021.

“This brass is also interesting for the notable attempts to fit it into cis-heteronormative expectations of history. Bennett writes “some have described the brass as a memorial to two children [despite them both living into adulthood]; others have imagined they were looking at two entirely separate brasses [despite the inscription referring to them both and their being connected]; and still others have fiddled with genealogies to minimize any direct relationship between the two women (Bennett,2008, p.131).” She attributed these manipulations to homophobic anxieties, which result in “bad history” and argues for the place of Elizabeth and Agnes in the “histories that modern… queers rightly seek from the past (Bennett, 2008, p.136,141).”

Woodley, 2021.

“The design suggests that no one — not Agnes Oxenbridge in pre-mortem requests, not Thomas Etchingham II and Robert Oxenbridge III acting on her behalf, and not the artisans in the workshop — shied away from representing the two women as an intimate couple. Indeed, the monument seems to have been designed with special emphasis on their warm affection. This affection was suggested, of course, by the simple fact of their joint brass, for most brasses with multiple figures remembered married persons—a motif generally understood as celebrating the closeness and fidelity of marriage. But the designers of this brass pushed beyond mere joint commemoration in stressing intimacy, for Elizabeth Etchingham and Agnes Oxenbridge were also deliberatelyshown facing each other, moving towards each other, and looking directly into each other’s eyes. Most contemporary joint effigies showed couples f acing the front,much like bodies laid in tombs, but Elizabeth Etchingham and Agnes Oxenbridge were portrayed in semi-profile, turned towards each other.”

Bennett, 2011.