04_Poetry

Printable zine version:

SOR JUANA INES DE LA CRUZ.

12 November 1648 – 17 April 1695.

b. Tepetlixpa, Mexico. d. Mexico City, Mexico

Sor Juana de la Cruz was born in 17th-century Mexico. By age 3, she had taught herself to read and write in Latin, by eight had begun composing and in her teen years learned the Aztec language of Náhuatl. When her parents refused her plan to attend university disguised as a man, she instead joined a convent, one of the only places she could pursue an education.

Cabrera, M. (c.1750) ‘Portrait of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.’ [Oil on canvas] At: Museo Nacional de Historia, Mexico City.

She transformed her convent cell into an intellectual salon, with a library of around 4,000 books, the largest collection in Mexico. She was a poet, philosopher and composer. She began an intimate relationship with Countess Maria Luisa de Paredes, inspiring many love poems by the sister. She was an outspoken advocate against misogyny and hypocrisy within the church, leading to the Bishop of Puebla condemning and forcing her into silence. Her letter "Respuesta a Sor Filotea” is hailed as the first feminist manifesto, it was not published until 1900. She died nursing fellow sisters through a plague.

MY LADY.

Let my love be ever doomed

if guilty in its intent,

for loving you is a crime

of which I will never repent.

*

LOVE OPENED A MORTAL WOUND.

Love opened a mortal wound.

In agony, I worked the blade

to make it deeper. Please,

I begged, let death come quick.

Wild, distracted, sick,

I counted, counted

all the ways love hurt me.

One life, I thought—a thousand deaths.

Blow after blow, my heart

couldn't survive this beating.

Then—how can I explain it?

I came to my senses. I said,

Why do I suffer? What lover

ever had so much pleasure?

In agony, I worked the blade

Wild, distracted, sick,

I counted, counted

all the ways love hurt me.

One life, I thought—a thousand deaths.

Blow after blow, my heart

couldn't survive this beating.

Then—how can I explain it?

I came to my senses. I said,

Why do I suffer? What lover

ever had so much pleasure?

*

DON’T GO MY DARLING

Don’t go, my darling, I don’t want this to end yet.

This sweet fiction is all I have.

Hold me so I’ll die happy,

thankful for your lies.

My breasts answer yours

magnet to magnet

Why make love to me, then leave?

Why mock me?

Dont brag about your conquest--

I’m not your trophy.

Go ahead: reject these arms.

That wrapped you in sumptuous silk.

Try to escape my arms, my breasts--

I’ll keep you prisoner in my poem.

This sweet fiction is all I have.

Hold me so I’ll die happy,

thankful for your lies.

My breasts answer yours

magnet to magnet

Why make love to me, then leave?

Why mock me?

Dont brag about your conquest--

I’m not your trophy.

Go ahead: reject these arms.

That wrapped you in sumptuous silk.

Try to escape my arms, my breasts--

I’ll keep you prisoner in my poem.

Biblio:

Cherry, K. 2022. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: Nun who loved a countess in 17th-century Mexico City. [online] Qspirit. Available at: <https://qspirit.net/sor-juana-de-la-cruz-nun-mexico/> (Accessed: October 10, 2022).

de la CruZ, J.I. (n.d) ‘Love Opened a Mortal Wound,’ Poets.org [Online]. Available at: <https://poets.org/poem/love-opened-mortal-wound>

de la Cruz, J.I., Peden, M. and Stavans, I. 1997. Poems, protest, and a dream. New York: Penguin Books.

Rupp, L. 2011. Sapphistries. New York: New York University Press.

In Zine Figures:

1. Escudo de monja depicting Inmaculada Concepción. (n.d.) [Oil on panel] At: Museo Soumaya.

2. Cabrera, M. (c.1750) ‘Portrait of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.’ [Oil on canvas] At: Museo Nacional de Historia, Mexico City.

Hind bint al-Nu’man & Hind bint al-Khuss.

c.582-602 B.C.E.

Mesopotamia.

Openwork furniture plaque with a striding, ram-headed sphinx (ca. 9th–8th century B.C.) [Ivory] At: The Met, New York.

Hind bint al-Khuss al-Iyādiyya (Also known as al-Zarqāʾ)(هند بنت الخس الإيادية) and Hind bint al-Nu'man (al-Hurqah)(هند بنت النعمان) were two pre-Islamic female poets.

Al-Hurqah is reportedly the daughter of al-Nu'man III ibn al-Mundhir, the last Lakhmid king of al-Hirah and a Nestorian Christian Arab mother. According to legend, fleeing marriage she found refuge with Al-Hujayjah (another female poet)

Due to oral tradition, in al-Isbahani’s alternative telling ‘Kitab al-Aghani’ it is Zarqä' al-Yamäma whom Hind bint al-Nu’man falls in love. Zarqä’ was semi-legendary for her extraordinary sight:

“Hind loved Zarqä' al-Yamäma, who was the first Arab woman to love another woman. As regards the latter, they say that she was able to spot an advancing army at a distance of some thirty miles.”

Cassarino, 2014, p.184.

Her work as a sentinel is unheeded, attackers ransacking the settlement of Gadïs and capturing Zarqä’. Their story ends:

“Zarqä' died some days later. When Hind [al-Hurqah] heard the news, she turned to religion, she wore sackcloth and had a monastery built, which took its name from her and where she lived until she died.”

al-Isfahani, 1900, p. 125.

In Ali ibn Nasr al-Katib's 'Encyclopedia of Pleasure' he writes of how al-Hurqah’s love for al-Zarqāʾ was a romantic ideal. After al-Zarqa’s death, al-Hurqah went into deep morning, ‘cropped her hair, wore black clothes, rejected worldly pleasures.’ She built the monastery in memory of al-Zarqāʾ and was buried beneath it’s gate.

The two are the first reported lesbians in Arab culture:

“Culturally speaking and in the context of medieval Arabic literary writing, sahiqat (lesbians)were associated rather with love and devotion, and at times they were even known to form an exclusive and supportive subculture. As a matter of fact, the origin of lesbianism, according to popular anecdotes in the Arabic literary tradition, is regularly traced back forty years before the emergence of male homosexuality to an intercultural, interfaith love affair between an Arab woman and a Christian woman in pre-Islamic Iraq.”

Amer, 2009, p.218.

“One might argue that the Arabic terms for "lesbianism" (sahq, sihaq, and sihaqa) and "lesbian" (sahiqa, sahhaqa, and musahiqa) refer primarily to a behavior, an action, rather than an emotional attachment or an identity. The root of these words (s-h-q) means "to pound" (as in spices) or "to rub,"

Amer, 2009, p216.

“Recovering the evidence of lesbianism and of lesbian-like attachments in the medieval Arabic tradition speaks thus to the emancipatory possibilities of the history of sexuality. Moreover, the medieval Arabic practices of homosexuality and lesbianism also challenge contemporary Western and Eastern (Arabic) assumptions about gender and, in particular, the binary constructions of masculinity and femininity.”

Amer, 2009, p.236.

Biblio:

al-Isfahani. 1900. Kitab al-Aghani 'The Book of Songs'. 2, p.125.

Amer, S. 2008. Crossing borders: Love Between Women in Medieval French and Arabic Literatures (The Middle Ages Series). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Amer, S. 2009. Medieval Arab Lesbians and Lesbian-Like Women. Journal of the History of Sexuality 18(2), p.215-236. Available at: <doi:10.1353/sex.0.0052>

Cassarino, M. 2014. INTERPRETING TWO STORIES OF THE "KITĀB AL-AĠĀNĪ": A GENDER-BASED APPROACH. Quaderni di Studi Arabi, [online] 9, pp.181-193. Available at: <http://www.jstor.org/stable/24640440 >

van Raphael, G. 2019. [Twitter] May 24. Available at: <https://twitter.com/AliaGvR/status/1131936939601477632?s=20&t=0kipuq-H0Aw02q0qExfEqw> (Accessed: October 5, 2022).

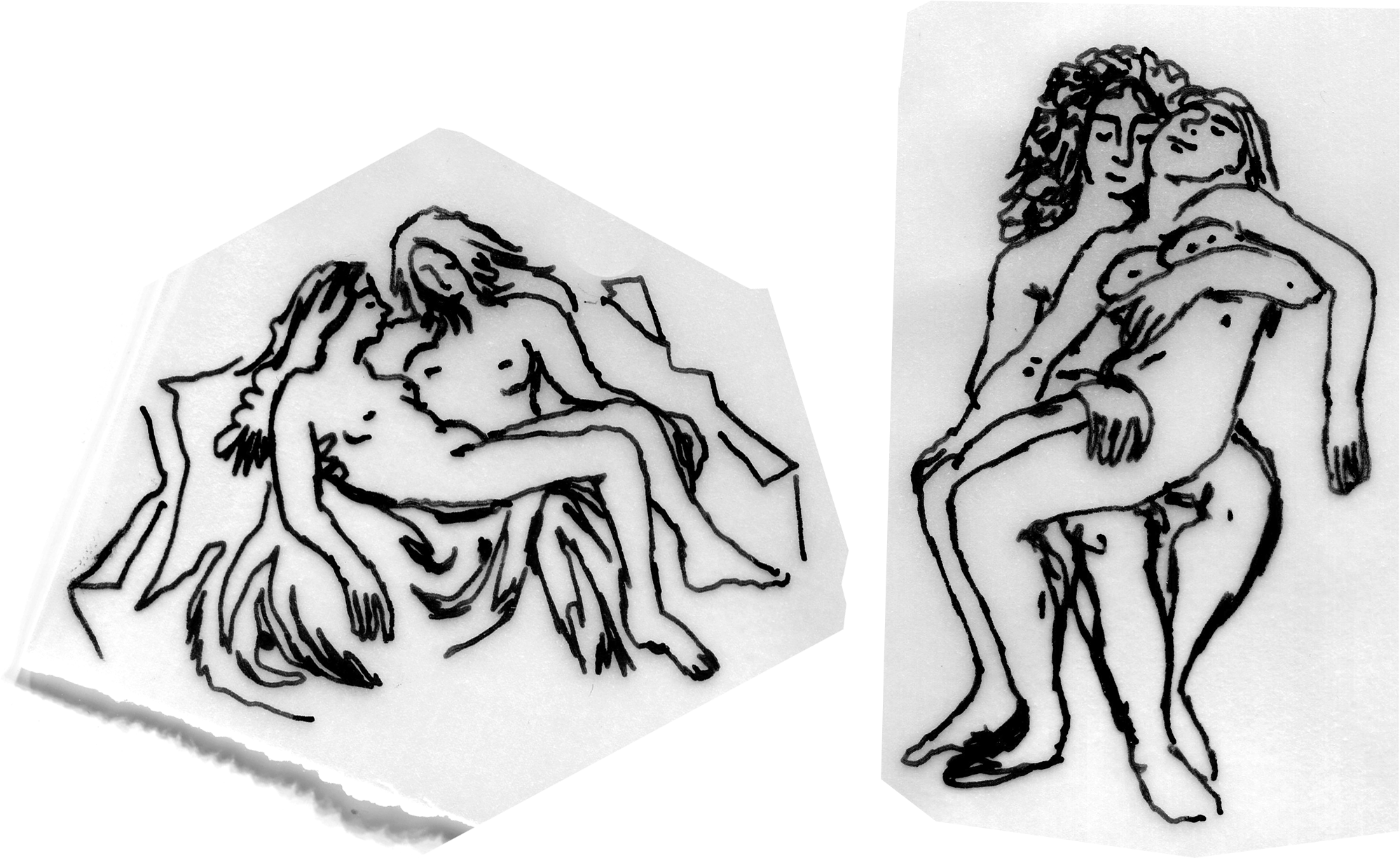

Ruth and Naomi.

c. 6th–4th centuries BCE.

Hermogenes Calderon, P. 1886. 'Ruth and Naomi' [Oil paint on canvas]

In the Book of Ruth, Naomi, her husband Elimelech and sons emigrate to Moab. Elimelech dies and the two sons marry, Ruth and Orpah. After a decade and the death of the two sons, Naomi decides to return to Bethlehem. It is here she tells her daughters-in-law to leave her and remarry. Whilst Orpah leaves, Ruth instead replies:

Ruth 1:16

RUTH REPLIED:

DO NOT URGE ME TO LEAVE YOU

OR TO TURN FROM FOLLOWING YOU.

FOR WHEREVER YOU GO, I WILL GO,

AND WHEREVER YOU LIVE, I WILL LIVE;

YOUR PEOPLE WILL BE MY PEOPLE,

AND YOUR GOD WILL BE MY GOD.

WHERE YOU DIE, I WILL DIE,

AND THERE I WILL BE BURIED.

MAY THE LORD PUNISH ME,

AND EVER SO SEVERELY,

IF ANYTHING BUT DEATH SEPARATES

YOU AND ME.

“The same Hebrew word (dabaq) is used to describe Adam’s feelings for Eve and Ruth’s feelings for Naomi. In Genesis 2:24 it says, “Therefore shall a man leave his father and his mother, and shall cleave unto his wife: and they shall be one flesh.” The way that Adam “cleaved” to Eve is the way that Ruth “clung” to Naomi.”

Cherry, 2021.

“The Book of Ruth does not detail the relationship between Ruth and Naomi; it simply presents us with an exceptional story of devotion…Cautious not to apply an anachronistic conception of lesbianism to the text, queer scholars seem to agree that the Ruth–Naomi dyad offers a powerful biblical example of same-sex intimacy.”

Presner, 2017.

“The very existence of Ruth and Naomi’s intimate relationship in the Bible, a thousands-of-years-old text, is significant and radical.”

Spivack, 2020.

Interestingly there are no weddings in the Bible, apart from the vows between Ruth and Naomi and David and Jonathan. So if looking for verses to use, you’d need to look to the love laments of two queer couples.

Biblio:

Cherry, K. 2021. Ruth and Naomi: Biblical women who loved each other. [online] Qspirit. Available at: <https://qspirit.net/ruth-naomi-loved-each-other/> (Accessed: October 2, 2022).

Preser, R. 2017. Things I Learned from the Book of Ruth. De/Constituting Wholes: Towards Partiality Without Parts, [online] pp.47-65. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.37050/ci-11_03> (Accessed: September 25, 2022).

Spivack, E. 2020. "Wherever You Go, I Go": Queerness in the Book of Ruth. [online] Jewish Women's Archive. Available at: <https://jwa.org/blog/wherever-you-go-i-go-queerness-book-ruth> (Accessed: September 25, 2022).

In Zine Figures:

3. Hermogenes Calderon, P. 1886. 'Ruth and Naomi' [Oil paint on canvas]

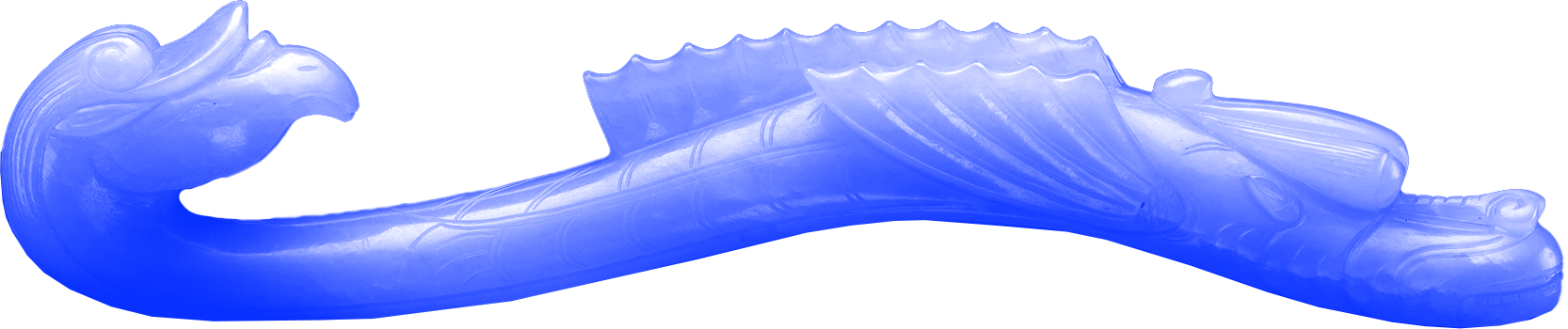

Wu Zao.

c. 1799-1862 CE.

China.

Wu Zao, is one of China’s greatest female and lesbian poets. The daughter and wife of merchants, she learnt to read, write, play music as well as paint. With the recorded lack of literary interest in her surroundings, all these talents were likely self-taught. Despite the pressures and expectations of a woman and wife, she became a prolific poet, playwright, artist and composer. In her opera ‘The Image in Disguise’ a woman cross-dresses, paints self-portraits and laments about the societal strictures of being a woman on her talents. Throughout her life she would have many romantic and sexual relationships with women, addressing multiple poems to female courtesans.

Garment hook in the shape of a phoenix.(c.19th century) [Jade (nephrite)] At: The Met Museum, New York. 02.18.475

FOR THE COURTESAN CH'ING LIN

On your slender body

your jade and coral girdle ornaments chime

like those of a celestial companion

come from the Green Jade City of Heaven.

One smile from you when we meet,

and I become speechless and forget every word.

For too long you have gathered flowers,

and leaned against the bamboos,

your green sleeves growing cold

in your deserted valley;

I can visualize you all alone

a girl harboring her cryptic thoughts.

You glow like a perfumed lamp

in the gathering shadows.

We play wine games

and recite each other poems.

Then you sing “Remembering South of the River”

with its heart-breaking verses.

We both are talents who paint our eyebrows.

Unconventional as I am,

I want to possess the promised heart of a beautiful woman like you.

It is spring.

Vast mists cover the Five Lakes.

My dear, let me buy you a red painted boat

and carry you away.

Pendant.(c.19th century) [Jadeite] At: The Met Museum, New York. 65.86.83.

“Despite the People’s Republic of China attempting to erase the long history of male and female homosexuality in China---dating all the way back to the Yellow Emperor of the 27th century BCE!---many, many records still survive. In the early dynasties, our knowledge of male homosexuality stems mainly from court records, many of which had separate sections for emperors and their male favorites. We also have a poetric tradition that spans almost all of Imperial Chinese history, though it isn’t always easy to suss out the gender of the person spoken about due to unique linguistic features in China. In the 16th-17th centuries, we finally start to get fiction that represents both male and female homosexuality in the form of books, short stories, and plays. Plus, lots of paintings!”

(History is Gay, 2018)

Biblio:

History is Gay. 2018. Homosexuality in Imperial China. [online] Available at: <https://www.historyisgaypodcast.com/notes/2018/2/4/episode-3> (Accessed: September 17, 2022).

Rexroth, K. and Zhong, L., 1972. Women Poets of China. New York: J. Laughlin by New Directions Pub. Corp. pp. 72-78

Wiles, S., Stefanowska, A., Ho, C. and Lee, L., 1998. Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women. Vol. 1: The Qing Period, 1644-1911 (University of Hong Kong Libraries publications ; no. 10). Routledge, pp.234–36.

Alice Dunbar Nelson.

July 19 1875 - September 18 1935.

USA.

Parker Bellsmith, R. (c. 1895) ‘Photograph of Alice Dunbar-Nelson’ [Photograph]

Scurlock, A. (c. 1915) ‘Photograph of Alice Dunbar-Nelson’ [Photograph]

Alice Ruth Moore Dunbar-Nelson was born in New Orleans to Patricia Wright, a seamstress and Joseph Moore, a merchant marine. At 17 she earned her teaching degree at the HSBU Straight University and at 20 she published her first collection of poetry and short stories ‘Violets and Other Tales.’ After studying English lit at Cornell in 1896, she wrote ‘The Goddess of St. Rocque and Other Stories’ just four years after her first.

Dunbar-Nelson, A. M. & Daniel Murray Collection. 1895. Violets and Other Tales. Boston, Mass.: Monthly Review. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/95233207/.

She was a prolific journalist and writer, all whilst teaching in local public schools (for 39 years). She is best known for her poetry, and being an intrinsic part in the flourishing of the Harlem Renaissance. Alice was an early activist in the Black women’s club movement, (Carbado, et al., 2012, p.17) and wrote for The Woman’s Era, the first US national newspaper written and published for and by Black women.

She was married three times, whilst also having numerous romantic affairs with other women. She began a relationship with Edwina B. Kruse. in 1907 Edwina wrote to Alice:

“I want you to know dear, every thought of my life is for you, every throb of my heart is yours and yours alone. I just can not ever let any one else have you.”

Edwina B. Kruse to Alice Dunbar Nelson

Whilst there are a few allusions to her sapphic desires, most are kept to her private diaries; on August 1, 1928, she wrote:

“Narka [Narka Lee-Rayford, of the National Federation of Colored Women] comes to the house for comfort. We want to make whoopee … Life is glorious. Good homemade white grape wine. We really make whoopee. Leitha and Narka strike up a heavy flirtation. My nose sadly out of joint. Something after two Narka starts to drive home alone, just as Bobbo [Dunbar Nelson's husband] comes up. Such a glorious moonlight night…

Carbado, et al., 2012, p.18.

Fay Jackson Robinson was her “little blue dream of loveliness.” The day they met Alice called “One Perfect Day” and on April 12, 1930 she wrote in her diary:

“You did not need to creep into my heart

The way you did. You could have smiled

And knowing what you did, you have kept apart

From all my inner soul. But you beguiled

Deliberately.”

Her diaries reveal:

"the existence of an active black bisexual network among prominent 'club women' who had husbands but managed to enjoy lesbian liaisons as well as a camaraderie with one another over their shared secrets.”

Faderman, 1992.

“And while African American lesbian or bisexual authors such as Angelina Weld Grimké and Alice Dunbar-Nelson had in fact been publishing politically engaged work since the late-nineteenth and early twentieth-century, this literature was either unconcerned with homosexuality or, when same-sex subject matter was incorporated, often left unpublished, as with Grimké’s love poems and Dunbar-Nelson's short stories. Although present-day black lesbian, gay, and bisexual fiction may have its origins in this body of fledgling literature, these early writings are not “gay-identified,” in the contemporary sense of the term. Nor would authors such as Grimké, Dunbar-Nelson, or Nugent have identified their own sexual orientation as such.”

Carbado, et al., 2012, p.3.