06_Transformation

Printable zine version:

Carmilla.

Le Fanu, S.

1872.

We owe a lot to Carmilla; Dracula, Twilight, but perhaps above all else the lesbian vampire trope. In 1872 the Irish author Sheridan Le Fanu published the gothic novella Carmilla (Bram Stoker’s Dracula would be published a full 26 years later.) In it, Laura lives a lonely childhood with her father in an Austria castle. She has visions of a beautiful stranger visiting her at night.

“I saw a solemn, but very pretty face looking at me from the side of the bed. It was that of a young lady who was kneel ing, with her hands under the coverlet. I looked at her with a kind of pleased wonder, and ceased whimpering. She caressed me with her hands, and lay down beside me on the bed, and drew me towards her, smiling; I felt immediately delightfully soothed, and fell asleep again. I was wakened by a sensation as if two needles ran into my breast very deep at the same moment, and I cried loudly. The lady started back, with her eyes fixed on me, and then slipped down upon the floor, and, as I thought, hid herself.”

(Le Fanu & Tracy, 2008, p.246)

This longing is punctured by the arrival of a stranger by way of the carriage accident. Laura is struck to find her stranger before her, the lovely but mysterious Carmilla. The two are instantly drawn together and embarking on a relationship of increasing emotional and sexual intensity.

"And when she had spoken such a rhapsody, she would press me more closely in her trembling embrace, and her lips in soft kisses gently glow upon my cheek.”

(p.264)

"I ran to her in an ecstasy of joy; I kissed and embraced her again and again.”

(p.285)

“if your dear heart is wounded, my wild heart bleeds with yours.... I live in your warm life, and you shall die - die, sweetly die - into mine.... I cannot help it; as I draw near to you, you, in your tum, will draw near to others, and learn the rapture of that cruelty which yet is love.”

(p.263)

Carmilla is a typical 18-year-old; she sleeps all day, refuses to join prayer and stays up much of the night. Carmilla’s reluctance to share any information about herself, along with a string of deaths in the local young women. This gives Laura cause for investigation leading to her discovery of Carmilla’s vampirism.

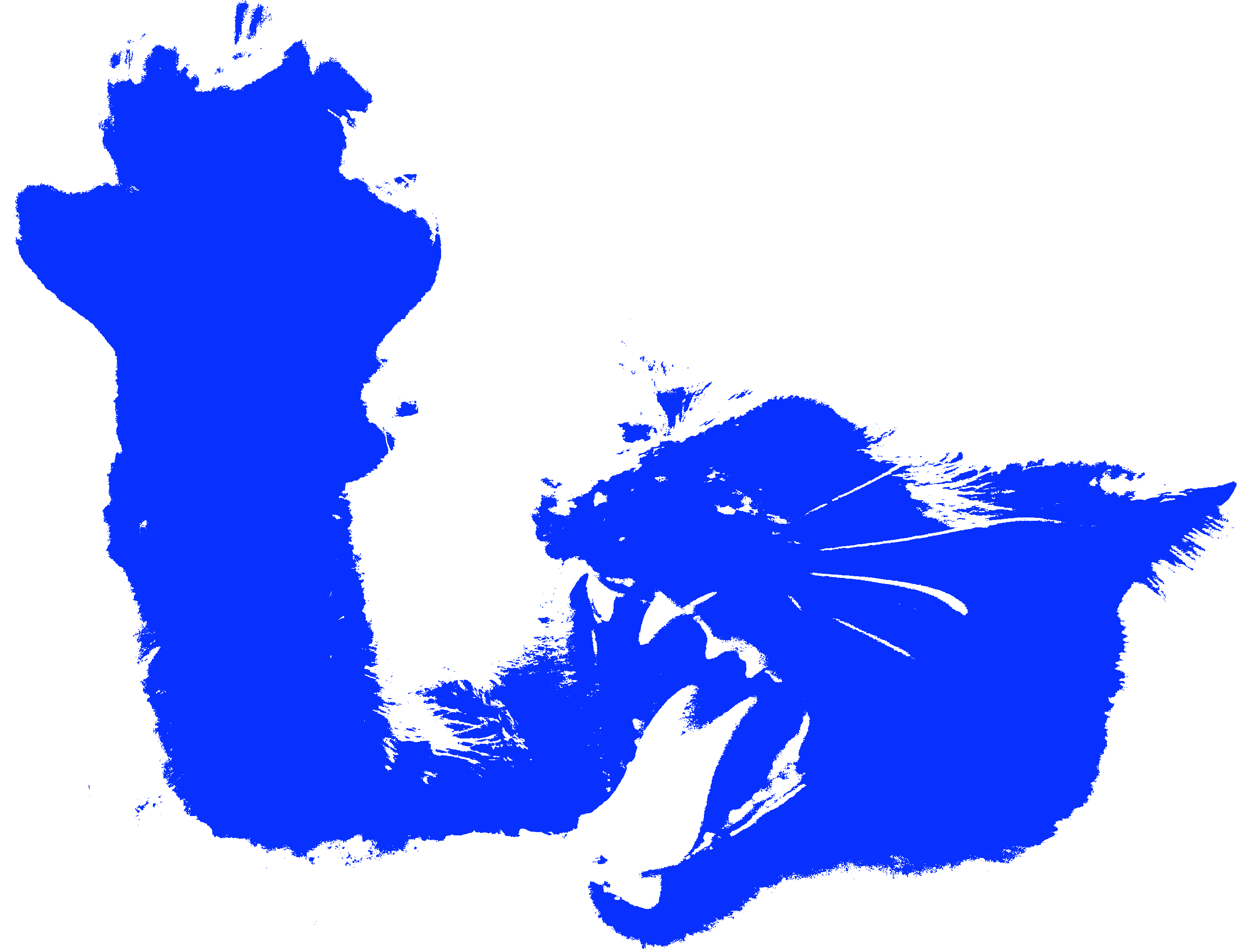

Keeping with the lesbian lexicon, Carmilla transforms into a cat, rather than a bat:

“But I soon saw that it was a sooty-black animal that resembled a monstrous cat. It appeared to me about four or five feet long for it measured fully the length of the hearthrug as it passed over it;”

(p.278)

“Although "Carmilla"'s denouement is ambiguous, Le Fanu refrains from heavy-handed moralizing, leaving open the possibility that Laura's and Carmilla's vampiric relationship is sexually liberating and for them highly desirable. The ontological change in Laura between the beginning of the narrative and the end is never reversed, suggesting that her shifting desires are, for her, healthy and vital”

(Signorotti, 1996, p.611)

In the last lines Laura still yearns:

"to this hour the image of Carmilla returns to memory with ambiguous alternations —sometimes the playful, languid, beautiful girl; sometimes the writhing fiend I saw in the ruined church; and often from a reverie I have started, fancying I heard the light step of Carmilla at the drawing-room door"

(Le Fanu & Tracy, 2008, p.319)

Horror and sexuality entwine throughout fiction. As a genre, horror has been employed as a vehicle for exploring social issues (Russo, 1987). Vampires as fictional monsters have been used to scapegoat multiple marginalised identities (Hughes and Smith, 2011). For the last century, the fear of female sexuality and liberation has incensed the interest in the lesbian vampire; the seductress, the heathen, the predator. Her queerness unnatural, devilish, wrong.

Despite this, there has always been a draw to vampires for the queer community; outsiders calling to one another. A change in the 70s came with a shift in politics, with the views of sexual ‘taboos’ shifting. The waters became murkier, the black and white villainy of these women becoming more questionable. Where before their unbridled/unquenched sexuality and emancipated lives might have been monstrous, it was now perhaps empowering.

From the outset, ‘Carmilla’ was always a surprisingly progressive, the desire between the two women is palpable and reciprocated. The genre it spawned is problematic in many ways, but also groundbreaking in a fair few, giving us some of the few instances of onscreen sapphic desire. It sowed a path that we are still fascinated with today, a trail of breadcrumbs that has lead to an unquenchable hunger.

Biblio:

Hughes, W. and Smith, A., 2011. Queering the Gothic. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Hulan, H. 2017. Bury Your Gays: History, Usage, and Context. McNair Scholars Journal, [online] vol. 21, no.1, pp 17-27. Available at: <https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair/vol21/iss1/6> [Accessed 4 January 2022].

Jönsson, G. (2006) “The Second Vampire: ‘filles fatales’ in J. Sheridan Le Fanu's ‘Carmilla’ and Anne Rice's ‘Interview with the Vampire,’” International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, 17(1), pp. 33–48.

Le Fanu, S. and Tracy, R. (2008) In A Glass Darkly. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Le Fanu, S. and Richardson, M (1945) in Novels Of Mystery From The Victorian Age. London: Pilot Press, pp. 573–628.

Le Fanu, S. 1872, ”Carmilla,” in In a Glass Darkly. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 1995.

Russo, V., 1987. The Celluloid Closet: homosexuality in the movies. New York: Harper & Row.

Signorotti, E. (1996) “Repossessing the Body: Transgressive Desire in ‘Carmilla’ and ‘Dracula,’” Criticism, 38(4), pp. 607–632.

Syrdal, K. (2022) 50+ lesbian vampire movies, Creepy Catalog. Available at: https://creepycatalog.com/lesbian-vampire-movies/ (Accessed: October 31, 2022).

The Celluloid Closet. 1995. [film] Directed by R. Epstein, J. Friedman and V. Russo. Los Angeles: Sony Pictures Classics.

Veeder, W. (1980) “Carmilla: The Arts of Repression,” Texas Studies in Literature and Language, 22(2), pp. 197–223.

In Zine Figures:

Collage featuring: Crypt of the Vampire (1946), Blood and Roses (1960), Succubus (1968), Lust for a Vampire (1971), Vampyros Lesbos (1971), Vampire Lovers (1971), Vampyres (1974), Nightmare Classics’ Carmilla (1989)

Iphis & Ianthe.

Ἶφις and Ἴφιδος

Crete, Greece

In classical Greek & Roman literature, Ovid’s Iphis and Ianthe is the only telling of lesbian-like desire. To set the scene, Ligdus’, tells the pregnant Telethusa that:

“A girl is more of a burden, and fortune has not given me the means to support one. So, though I pray that it should not happen, if a girl is born, then she must be put to death.”

Moore, 2021, p97.

Telethusa is visited by the goddess Isis, who advises her to keep the child no matter what. When the time comes, with the help of her midwife, Telethusa disguises her child and raises them as a son named Iphis (which interestingly is a gender neutral name.) Iphis is bethrothed to Ianthe and the two fall quickly and madly in love. “as a result, love touched their innocent hearts and wounded both alike.” Here we learn of Iphis’s lament.

The story is framed from Iphis’ perspective. Iphis is aware of the circumstances of her birth and though raised a boy, identifies still somewhat as a girl (pronouns used differ between and within translations). Her sadness is that the ruse will soon be up and that her love for Ianthe is unnatural and fated never to be.

“Why then not summon all your mettle, Iphis?

Return to your own self; extinguish this

flame that is hopeless, heedless, surely foolish.

For you were born a girl; and now, unless

you would deceive yourself, acknowledge that:

accept it; long for what is lawful; love

as should a woman love!”

(Mandelbaum 319)

“Before this denouement, however, Iphis anticipates a wedding at which there will be no groom, 'Just two brides" ("qui ducat abest, ubi nubimus ambae," 9.763), and she confronts the intractable problem of comprehending a nameless desire.' Despite her undeniable emotional and erotic attraction to Ianthe, Iphis is confounded in her efforts to represent or express what she feels. The difficulty she faces should be a familiar one, though, for it is not unlike the problem that we encounter when reading her story, especially if we try to understand the elusiveness of her desire in an historically sensitive manner.”(Walker, 2006, p205.)

A different, but no less valid reading could be that Iphis is a young trans man and what he laments is gender dysphoria. In the context of the time, ‘natural’ sexual activity is phallocentric and penetrative, the ‘unnaturalness’ of his desire for Ianthe is what society dictates as compatible for fertility.

Telethusa brings her child to the temple of Isis and together they pray for a solution that would allow Iphis and Ianthe to marry. Isis answers their prays by transforming Iphis:

“Her face lost its fair complexion; her hair seemed shorter, plain and simple in style, her features sharpened and her strength increased. She revealed more energy than a female has—for she who had lately been a maiden had become a man!”

Moore, 2021, p.99.

“Ovid may or may not have believed in a performative model of gender identity and sexuality. It seems likely that he did at least to some extent, as likely also did his audience. And he has certainly embedded his culture’s sense of negativity toward female same-sex relations, alongside a heteronormative, masculine ideal, within his narrative.”

Moore, 2021, p.111.

“There is continued conversation as to whether Ovid is anti- or pro-lesbian.”

Pintabone, 2002.

"Walker (2006) argues that the Iphis story both gives and revokes “lesbianism”: while the possibility of something like lesbianism is allowed to emerge in readers’ minds, Ovid never allows it to fully materialize.”

Kamen, 2012, p.22.

In the end, though it is a story about how two people who love each other are able to circumvent societal strictures to spend their lives together. Iphis is still an important figure in the canon of trans & sapphic history, and one that can transform with each individual reader.

"o Iphis," says the narrator, "you who were a girl so recently/are now a boy" (Mandelbaum 321; "nam quae/femina nuper eras, puer es," 9.790-91). And, indeed, by story's end, the goddess Isis has transformed Iphis's anatomy, thereby resolving all of the obstructions that have prevented her and Ianthe from coming together in marriage and in body. Yet, before the happily-ever-after, Iphis voices a long and grief-stricken lament. She speaks of the intensity of her desire for the girl Ianthe, but she can only understand that desire in terms of a heteronormative logic of physical complementarity. Because it cannot be consummated in a penetrative fashion, Iphis's desire confounds both cultural and natural intelligibility.

Walker, 2006, p.209.

“In the context of historic literature, one of the most valuable legacies of Iphis and Ianthe is that continuing interpretations and variations on the story provide a context for exploring the possibility of desire between women. Many of those later explorations take the story in entirely different directions. But it establishes a precedent that has proven troubling across the centuries: that of setting lesbian and transmasculine narratives in competition with each other. We’re still dealing with the legacy of that framing.”

Jones, 2016.

Biblio:

Begum-Lees, R. 2020. “Que(e)r(y)ing Iphis’ Transformation in Ovid’s Metamorphoses,” in Surtees, A. and Dyer, J. (eds) Exploring Gender Diversity in the Ancient World. Edinburgh University Press, pp. 106–117.

EJB. 2021. Iphis: LGBTQ+ representation in Ovid and beyond, Women in Antiquity. Available at: <https://womeninantiquity.wordpress.com/2021/04/01/iphis/> (Accessed: September 20, 2022).

Jones, H.R. 2016. Queer Fantasy Roots: Gender Transformations in Ovid's metamorphoses, Queer Sci Fi. Available at: <https://www.queerscifi.com/queer-fantasy-roots-gender-transformations-in-ovids-metamorphoses/?cn-reloaded=1> (Accessed: September 22 ,22).

Kamen, D. 2012. “Naturalized desires and the metamorphosis of Iphis,” Helios, 39(1), pp. 21–36. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1353/hel.2012.0000>

Moore, K. 2021. “The Iphis Incident: Ovid’s Accidental Discovery of Gender Dysphoria,” ATHENS JOURNAL OF HISTORY, 7(2), pp. 95–116. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.30958/ajhis.7-2-1>

Ovid and Mandelbaum, A. 1995. The Metamorphoses of Ovid. San Diego: Harcourt Brace. p.319

Pintabone, D.T. 2002. "Ovid's Iphis and Ianthe: When Girls Won't Be Girls” in Rabinowitz, Nancy Sorkin & Lisa Auanger eds. 2002. Among Women: From the Homosocial to the Homoerotic in the Ancient World. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Walker, J. 2006. Before the Name: Ovid's Deformulated Lesbianism. Comparative Literature, [online] 58(3), pp.205-222. Available at: <https://www.jstor.org/stable/4125343>.

In Zine Figures:

1. Boissonnas, F. 1903. Οn the Sacred Rock of the Acropolis, Athens. [Photograph]

Roman de Silence.

c. 1200s.

Cornwall.

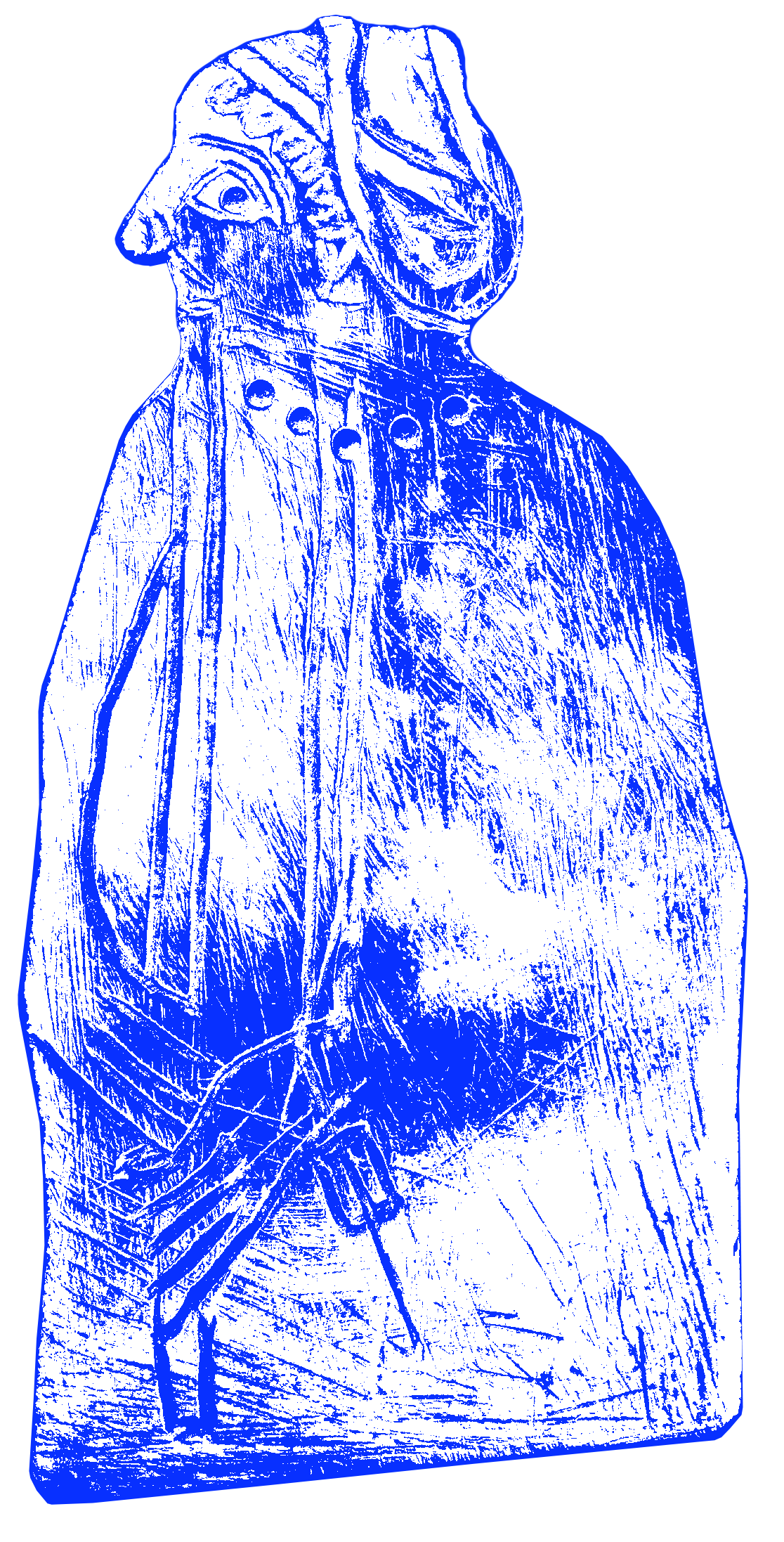

de Cornuälle, H (c, 13th century) ‘Silence Dressed as a Young Boy‘ in ‘La Romance de Silence’ [Manuscript] University of Nottingham, MS WLC/LM/6, f. 203r

In the thirteenth-century tale Roman de Silence, a child is born to the Cador, Earl of Cornwall and Eufemie (whose name means ‘use of good speech’ aka euphemism) Without any other children and the weight of patriarchal inheritance, the parents decide to raise their child a boy, named Silence. Reaching puberty, Nature personified arrives to chastise him for hiding his biology. Nurture turns up to argue, but it is not until Reason appears to convince Silence to remain as is. And so he does, continuing to train as a knight, but not before running away with two minstrels for four years. When he returns, he joins the royal court as a knight.

The Queen Eufeme (whose name means ‘alas! woman’. Not to be confused with his mother Eufemie) attempts to seduce Silence but he rebuffs her. The Queen accuses Silence of assaulting her, and the Kings sends him to France on the task of capturing the wizard Merlin. This is seen as an impossible task for a knight as Merlin can only be caught by ‘the trick of a woman’.

Silence catches Merlin, who in turn outs Silence to the court. The King has the Queen executed and at this point we also learn of the Queen’s secret lover who had been disguised as a nun. Silence from then on (if by choice or instruction) lives as a woman and marries the King.

Le Roman de Silence is written in octosyllabic verse and is attributed to Heldris de Cornuälle. He opens the story by telling the audience that the arts are underpaid and unappreciated. Not much has changed since.

This text exists as a single manuscript, found in Walton Hall, Nottingham in 1911. It was found in a box marked ‘unimportant documents’

“Medieval thought does assume that there’s such a thing as a “woman” and a “man,” but prior to the emergence and institutionalization of concepts like “the normal,” distinctions between the two fail to map onto the gender binary as we experience it today. … Imaginative literature, however, offers affordances to explore what the world might be rather than what it is, and can sometimes function as the space where the nature of sex and gender gets worked out in a relatively consequence-free way.”

Raskolnikov, 2021, p.178.

"Simply by setting up a romance’s main protagonist to be raised to perform successfully as a man and (therefore) repeatedly doubting that they have the ability to succeed as a woman, Heldris of Cornwall denaturalizes “male” and “female.” The romance demands that we notice this: Heldris renders both “male” and “female” as things that have to be learned, skill sets and sets of habits that, in turn, mark the body (as when living as male renders Silence’s mouth “too hard”).

Raskolnikov, 2021, p.180.

“The question of what constitutes the “truth” of sex and gender functions as the driving force for much of the narrative, which hinges strongly on the status of “the secret,” a concept that very obviously gets coded within the romance as “silence,” both as the protagonist’s name and as an absence of sound.”

Raskolnikov, 2021, p.180.

Biblio:

Boulanger, J. (2018) “Women Reading Silence in a Time of Social Fracture,” University of Notre Dame's Medieval Institute, 12 October. Available at: http://sites.nd.edu/manuscript-studies/tag/roman-de-silence/#_ftn1 (Accessed: October 3, 2022).

Raskolnikov, M. (2021) “8. without magic or miracle: The romance of silence and the prehistory of genderqueerness,” Trans Historical, pp. 178–206. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501759529-011.

Steenson, K. (2018) “Silence,” University of Nottingham Blogs / Manuscripts and Special Collections, 15 August. Available at: https://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscripts/2018/08/15/silence/ (Accessed: October 3, 2022).

Inanna.

c. 8000-2000 B.C.

Mesopotanian (present-day Iraq and northeastern Syria).

“Inanna erupts in new forms periodically. In our era, she’s overdue”

Grahn, 2021.

'Queen of the Night' [Fired clay plaque] At The British Museum, London. 2003,0718.

Inanna is the Mesopotamian deity of sex, justice, war and fertility, She is a goddess of rebirth, reinvention, her myths and legends go as far back as 4000 years ago, and have echoed throughout time; a devastating flood, her death and return after three days, a paradise garden.

'Woman wearing a cylinder seal, playing a flute' (c. 2600–2500 B.C.) [Shell inlay]

‘The Adda Seal’ depicting the deities Inanna, Utu, Enki, and Isimud (c. 2300 BC) [Greenstone Akkadian cylinder seal]

A hymn to Inanna recounts:

She takes the great crime from their body

She places a hand upon their brow, calls them pilipili

breaks the lance, gives them a weapon as for a man’s heart

She does not esteem he whose name

She called; upon approaching the woman

She cuts the weapon, gives her a lance

reed marsh man, nisub, reed marsh woman, She punishes, groan…

lualedde, transformed pilipili, kurĝarra, saĝursaĝ

lamentation, song…

“A reed marsh is a place that doesn’t fit into a simple definition. It’s not dry land, but it’s not exactly a river. It’s not completely fresh water or salt water. It’s a murky, in-between place that blurs the line between the solid and the fluid — a symbolic no man’s land that defies categorization.In these myths, the reed marsh man and reed marsh woman blur the line between male and female.”

Benedict, 2015.

“In a “headoverturning” ritual in Inanna’s temple, women and men were given the clothes and tools of the other gender and became shamanic temple officials. Inanna referred to them as “reed marsh” people, placing them back into Sumer’s creation story, which had divided people into binary genders, as reeds in the marshes weave together different elements. “Other Sumerian names for androgynous, cross-dressed, or hermaphroditic people were galaturra and kurgarra; they also performed elegies and lamentations in Inanna’s temple” (118). Inanna was herself androgenous, possessing both the cloak of women and the mace of men, and associated with both female love and beauty through the third brightest evening star, and the male warrior-related third brightest morning star.”

Boyd, 2021.